Trade-offs in trading

Leasing aircraft often seems an easy option but care needs to be taken. Mario Pierobon reports.

In the early days of commercial aviation it was very much the case that airlines would buy aircraft rather than lease them. Since aircraft leasing companies began to develop critical mass in the 1980s, the leasing of aircraft has become a common option. Nowadays airlines making fleet planning decisions have to consider whether to buy or lease their aircraft assets, and as this decision making trade-off is never a perfect science, we reached out to industry experts to identify some best practices to deploy in the current economic environment for aircraft acquisition.

A sizeable proportion

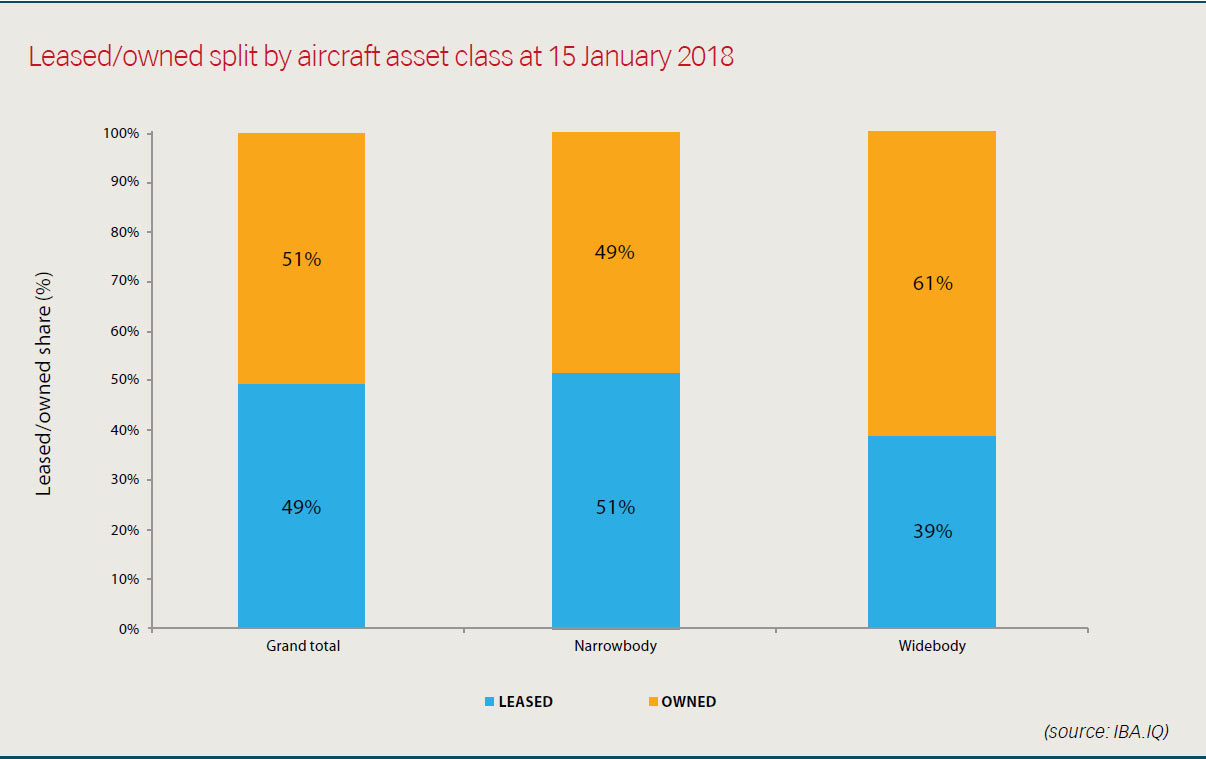

The global commercial fleet today consists of 29,400 aircraft, both active and parked. “The percentage of those leased is still growing and is currently 45%, up from 2% in 1980. Growth has been spectacular but is now levelling out as operators balance their fleets with a mix of owned and leased aircraft. While the top line figure is 45%, there are differences among both aircraft types and geography. In the long term, leasing can be a more expensive option so it makes sense to purchase aircraft if possible, when comfortable with the technology and price,” says Paul Lyons, Head of Advisory at IBA.

In absolute terms, the number of leased aircraft is currently approaching 11,000 units of all types, but the narrowbody market comprises over 7,000 units and accounts for two thirds of the total. Widebody leasing accounts for nearly 2,000 aircraft, and the remainder is roughly equally split between regional jets and turboprops. “Almost nobody believes that aircraft ownership will ever disappear, and as strange as it might seem, TrueNoord would not be alone in not wishing aircraft ownership to dwindle to a small portion of the total commercial airliner fleet. There are several reasons for this which include the fact that owning a portion of their fleets demonstrates that airlines are both financially and operationally committed to a type for the long-term, and have the appropriate infrastructure to maintain them,” says Angus von Schoenberg, Industry Officer at regional aircraft lessor TrueNoord. “Furthermore, the evidence to date shows that leasing penetration of popular aircraft types tends to stabilise at around 40-45% of the total fleet. Narrowbodies on lease have been in this range for some years with lower penetration rates for widebodies and regional aircraft. In the case of widebodies, high transition costs between lessees have always been a barrier to the growth of leasing, while regional aircraft leasing has only been adopted in a scalable way over the last decade. For this reason, TrueNoord and others see this sector as less mature than the larger aircraft segment, thereby offering more scope for further growth.”

Dealing with low interest rates

In recent years, low interest rates have proven to be widely available globally and across industries. To a degree low rates have led cash rich airlines to revert to buying aircraft assets instead of leasing them. “There are clear benefits of ownership if you are considering new generation narrowbodies long term. These include cheaper debt – if you are an established airline – better OEM support and lower total cost of ownership. However borrowing capacity and cost of capital on a risk adjusted basis will still make it uneconomic for many airlines to own aircraft going forward. We have supported a number of younger airlines who having initially leased given their relative credit risk, are now in a stronger negotiating position as an established

airline,” says Lyons.

Whilst, from the one end, low interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing for airlines, this also applies to lessors – so airlines can benefit through lower lease rates. Lessors typically finance their acquisitions of aircraft with a mix of equity and debt, and the latter usually amounts to 70-80% of the total purchase price. “In recent years, not only has the cost of debt been at historically low levels, but also the investor community has piled into narrowbody aircraft in particular as an attractive asset class, so the cost of equity has also reduced substantially. This has enabled quality, cash rich airlines to secure extraordinarily low lease rates. While the appetite for regional aircraft has been less, our investor profile demonstrates that equity can now also be attracted to the regional aircraft segment,” says von Schoenberg.

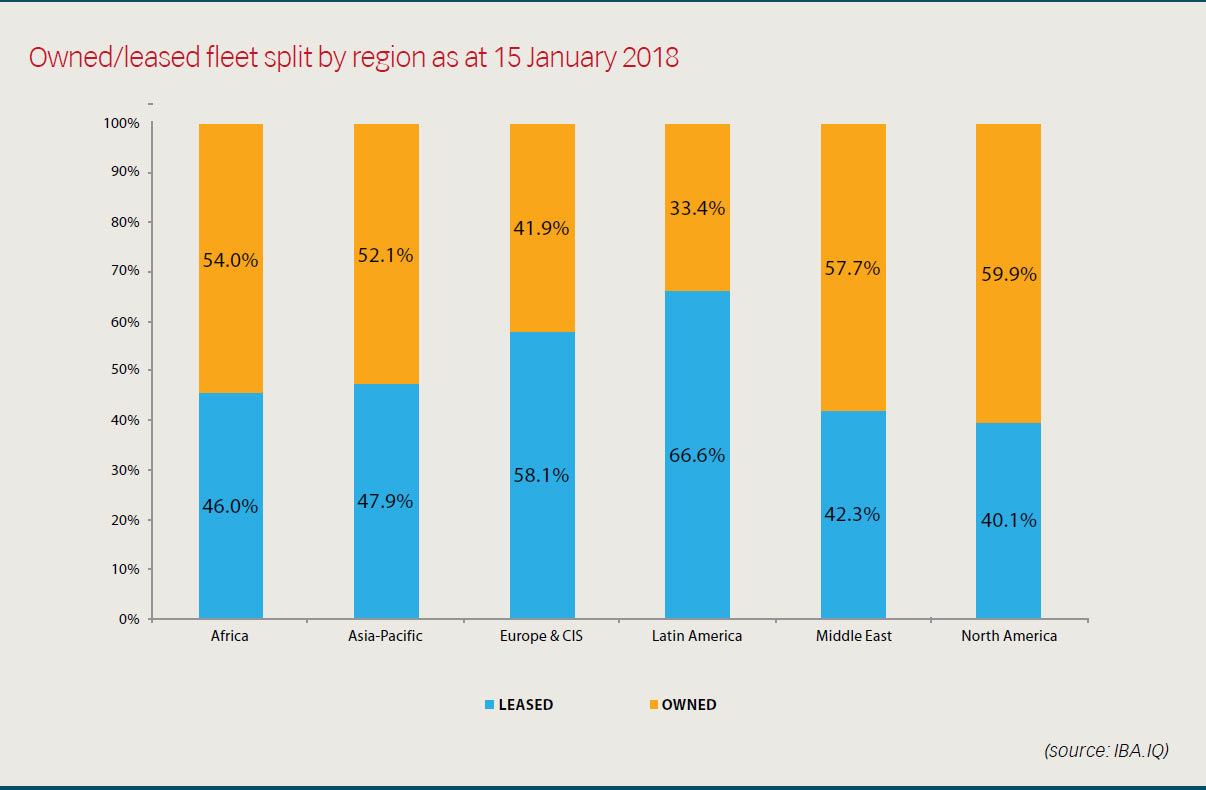

The proportion of aircraft that airlines lease depends on their strategy. “Larger top tier carriers have the luxury of choice. At the extremes, American Airlines leases the largest portion of its fleet with over 400 aircraft leased, while Lufthansa chooses to own the majority. However, in practice most major airlines opt for a mix of owned and leased aircraft,” notes von Schoenberg. “In the case of less good airline credits, the availability of leasing solutions or debt may influence how their aircraft are financed. In general, aviation finance lenders are more selective than lessors on their credit quality requirements, although many are happy to lend to lessors who then lease to the weaker credits on the basis that the lessor’s equity ranks junior to their loan exposure. Accordingly, some airlines lease rather than own due to lenders’ reluctance to engage. However, in other cases some carriers that have a strong presence in a local market but would be considered weak at an international level, can access attractive funding from local lenders. This then favours ownership.”

Pros and cons

In general, according to Lyons, the pros of leasing include flexibility, reduced capex, no asset risk and, if the OEM purchases in bulk, access to latest generation aircraft at lesser cost and with no waiting list. Conversely, the cons of leasing are that the airline cannot benefit from any equity value in the aircraft, lease terms might be constraining, reserves and maintenance require very careful planning, and redeliveries can often be challenging. In addition, balance sheet advantages are reducing with International Financial Reporting Standard 16 (IFRS16). The objective of IFRS 16 – which will be effective for annual reporting periods beginning on or after 1 January 2019 – is to report information that faithfully represents lease transactions and provides a basis for users of financial statements to assess the amount, timing and uncertainty of cash flows arising from leases. To meet that objective, a lessee should recognise assets and liabilities arising from a lease. “Historically, a major driver of the lease-versus-buy decision had been the desire to acquire aircraft off-balance sheet. However the pending changes to accounting rules that under IFRS16 will require all leased aircraft to be on-balance sheet, removes this motivation. This driver was always more common in North America where structured long-term operating leases with lease terms exceeding twelve years existed,” says von Schoenberg.

The lease-versus-buy strategy is primarily driven by attitudes to residual value and fleet management flexibility. “Furthermore, operating leases allow 100% of the acquisition cost to be financed by a third party whereas other forms of financing rarely exceed 85%. Depending on how airlines wish to deploy their capital (particularly fast growing low cost carriers) rapid growth can often be greatly facilitated by operating leases so that scarce capital resources can be deployed to finance the operations associated with expansion,” says von Schoenberg. “Many airlines take the view that residual value is a key risk when aircraft are owned, particularly if they are not committed to the type long-term. Furthermore, the disposal of unwanted aircraft when they are no longer required also consumes substantial management time and resources that can be more effectively employed managing the airlines’ operations. Operating leases pass this residual risk to an unconnected third party. In addition, operating leases allow for planned fleet flexibility. If an airline manages its lease maturity profile to allow for a number of aircraft to be returned in any given year, it can scale back its operations effectively to manage any industry downturn, or negotiate lease extensions/acquire additional aircraft on lease, if its business grows.”

A possible disadvantage of leasing is that, depending on the airline’s average cost of capital, leases can be more expensive than owning aircraft. In addition, if market demand is strong, the airline loses the benefit of the aircraft’s residual value. “There are also certain operational disadvantages. For example, in a weak market, an airline cannot return an aircraft early as it is bound by the terms of the lease whereas an owned aircraft can be sold at any time (although, in a depressed market, airlines may not realise the expected residual value). Conversely, in a strong market, an airline cannot assume that a lease can be extended as the lessor may want its aircraft back to place more profitably elsewhere. At a practical level, the need to return the aircraft in a certain return condition at the end of a lease can also be a partially hidden risk and cost,” says von Schoenberg.

Decision making factors

There is a certain set of parameters for airlines to assess when deciding whether to buy or lease an aircraft. “A key area is the importance of the aircraft type to its fleet, whether the aircraft is pivotal or critical to the operations. Another consideration should be given to the length of ownership and the flexibility of the fleet. If you know you are keeping it for more than 12 years, then ownership becomes more viable. In-house maintenance expertise is also important as it can further reduce ownership costs rather than outsourcing,” says Lyons. “The length of the waiting list should be considered in light of the fact that leasing might be a quicker way to access newer-generation aircraft. Capex also plays a part in that the choice between lease and buying is only a choice if you have adequate capital to purchase. Finally residual risk, especially in the widebody sector, needs very careful consideration.”

In the regional aircraft context in particular, there is a further option to consider in addition to buying and leasing. If an airline wishes to operate a regional aircraft fleet, for example, in order to feed its larger aircraft services, it can also choose to wet lease such a fleet by means of a capacity purchase agreement (CPA) or aircraft, crew maintenance and insurance (ACMI)

arrangement to meet its need for a certain type of lift. “While leasing such a turnkey operation might look expensive, by the time the lower crew costs of a typical regional airline are factored into the total costs, such an arrangement can be economically attractive to major airlines. This model has been widely adopted by US majors for regional flying and is gaining traction in Europe. Ultimately, such a model could evolve into virtual airlines,” says von Schoenberg.

From an economic standpoint, airlines need to compare the costs of borrowing up to 80% of the aircraft price and the cost of its capital for the remaining 20% along with its view on residual values, with the costs of leasing the aircraft. “Leasing is often perceived to be more expensive than loans or finance leases. While it is true that lessors need to be remunerated for taking residual value risk, lessors often have greater buying power than airlines as they typically place relatively large orders with OEMs resulting in cheaper initial aircraft costs. Furthermore, lessors’ cost of capital and borrowing costs can also be lower than those of many airlines. When all these elements are combined the economic case for leasing can be compelling,” says von Schoenberg. “With regard to both leasing and buying, scheduled maintenance costs should also be considered. In the case of a lease, the lessee will either need to pay monthly maintenance reserves, or provide lease end compensation for time consumed during the lease since the last applicable maintenance event.”

As a last consideration it should also be noted that there is also a substantial difference between larger and smaller airlines. “Compared to large operators, smaller carriers are often deficient in the financial resources to make down payments on aircraft and lack the time and knowledge to tap the wider financing market. Often this drives the management of smaller carriers to be more opportunity driven when lessors offer solutions. In this context, lessors including TrueNoord, can often become a partner in the fleet-planning process by offering appropriate solutions,” says von Schoenberg

19 February 2018